Today marks Abraham Lincoln’s 202nd birthday. I really don’t know what I could add that hasn’t already been said about our first Republican president and one of our greatest presidents. So many publications have been written about Lincoln, from his humble upbringing to his tragic death and everything between, particularly the significance of his presidency, some with praise, some with reproach. But without doubt, even in the most trying times of our nation’s history, Lincoln remained committed to the guidance of Natural Law and the idea instilled in our Declaration that “all men are created equal.” And perhaps fittingly so, as those difficult times during our Civil War absolutely transformed our Nation and our ideals in a different but reflective way as those first shots that established this magnificent Country.

One of the most interesting articles that I came across in deciding what to discuss on this day came from Andrew Ferguson, author of Land of Lincoln: Adventures in Abe’s America, and an article he wrote a few years back discussing what Lincoln means to Americans today.

What Does Abraham Lincoln Mean to Americans Today?

http://span.state.gov/nov-dec2009/eng/11-16_What_does_Lincoin.html

The last section of this article particularly caught my attention, so that’s what I thought I'd share today…

Expressing the American experiment

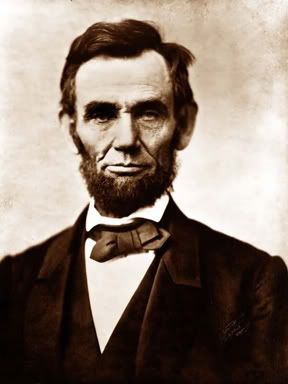

For nearly a century, historians and sociologists have tried to explain the historical infatuation that could result in such endearing absurdities. The reasons they’ve come up with are often clever and sometimes even plausible. Lincoln continues to fascinate his countrymen like no other historical personage, we’ve been told, because he was the first such personage to be commonly photographed: He is thus more real to us than great figures from earlier times can be. And it’s true that Lincoln was exquisitely sensitive to the ways in which he presented himself to the public, including through the use of the then-new photographic art. He seldom passed up a chance to have his likeness made. Thanks to that craftiness, we seem to know him in a way we could never know George Washington or Thomas Jefferson.

Even so, goes another argument, no matter how familiar we are with his face, with the sad eyes and tousled hair, Lincoln is tantalizingly and finally unknowable; it’s this mystery that draws us back to the melancholy, humorous, intelligent, reserved, distant, and kindly man that his acquaintances described. Other historians have said our infatuation with him is rooted in the drama of his personal story: Born in abject poverty to become one of the great men of human history, Lincoln embodies the “right to rise” that Americans claim as their birthright. Still others credit his enduring fame to his assassination on Good Friday, a shock from which the country never quite recovered. The most sober-minded of our theorists say we’re obsessed with Lincoln because he presided over, and somehow exemplifies, the greatest trauma of American history, a civil war that reinvented the United States into the country we know today.

There’s truth in all these explanations, I suppose, but it’s the last one, in my opinion, that comes closest to being the comprehensive truth. I live not far from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., that grand, photogenic temple on the banks of the Potomac River that is home to the “iconic Lincoln.” Researching my Lincoln book, spending time with scholars and collectors and obsessives and being introduced by each of them to yet another privatized Lincoln, a Lincoln pieced together from their own preoccupations, I was always glad to return home and pay the memorial a visit: to see this singular and solid Lincoln, the enduring Lincoln that every American can lay claim to.

The memorial is the most visited of our presidential monuments. The strangest thing about it, though, is the quiet that descends over the tourists who climb the wide sweeping stairway and step into the cool of the marble chamber. Before long their attention is drawn to one or both of the two Lincoln speeches etched in the walls on either side of the famous statue. After all this time I am still astonished at the number of visitors who stand still to read, on one stone panel, the Gettysburg Address, and, on the other, Lincoln’s second inaugural address.

What they’re reading is a summary of the American experiment, expressed in the finest prose any American has been capable of writing. One speech reaffirms that the country was founded upon and dedicated to a proposition—a universal truth that applies to all men everywhere. The other declares that the survival of the country is somehow bound up with the survival of the proposition—that if the country hadn’t survived, the proposition itself might have been lost. Sometimes the tourists tear up as they read; they tear up often, actually. And watching them you understand: Loving Lincoln, for Americans, is a way of loving their country.

That’s what Lincoln means to Americans today, and it’s why he means so much.