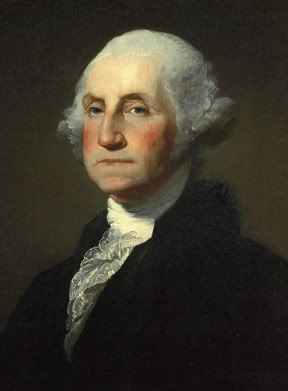

Yesterday was President’s Day, and today we celebrate George Washington’s 279th birthday! What a long road this nation has travel since our first President, and, particularly in our present state, what lessons we can continue to learn from the enduring legacy of such a humble and faithful public servant.

The profound greatness of George Washington has been celebrated throughout the annals of history and multitudes of publications. His leadership is demonstrated throughout his life, from a young British colonial officer, rising to military prominence as Commander of the Continental Army, to urging the establishment of a government capable of securing the liberties won during the Revolution and onto presiding over America’s Constitutional Convention. His military and political careers were substantial prior to being selected as the first President of the United States. But upon the unanimous approval of his colleagues in 1789, Washington expressed a great reluctance to again enter public service when the nation called upon him to serve as chief executive under the newly adopted Constitution:

“... my movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution: so unwilling am I, in the evening of a life nearly consumed in public cares, to quit a peaceful abode for an Ocean of difficulties, without that competency of political skill, abilities and inclination which is necessary to manage the helm. I am sensible, that I am embarking the voice of my Countrymen and a good name of my own, on this voyage, but what returns will be made for them, Heaven alone can foretell. Integrity and firmness is all I can promise; these, be the voyage long or short, never shall forsake me although I may be deserted by all men. For of the consolations which are to be derived from these (under any circumstances) the world cannot deprive me.”

From 1789 – 1796, he held the highest office in the land. The office of president had in fact been designed with his virtues in mind. Humbled, yet steadfast, Washington was aware that virtually every action he took established precedence. And with this realization, he maintained a reverent tone for this office, remembering from the beginning, and at all times, the role of Providence:

“Such being the impressions under which I have, in obedience to the public summons, repaired to the present station, it would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official act my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States a Government instituted by themselves for these essential purposes, and may enable every instrument employed in its administration to execute with success the functions allotted to his charge. In tendering this homage to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own, nor those of my fellow-citizens at large less than either. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than those of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency; and in the important revolution just accomplished in the system of their united government the tranquil deliberations and voluntary consent of so many distinct communities from which the event has resulted can not be compared with the means by which most governments have been established without some return of pious gratitude, along with an humble anticipation of the future blessings which the past seem to presage.”

Mindful of the importance of his decisions, he enlisted highly qualified men to form his cabinet and often called upon them for advice. And even in these times preceding political parties, two of Washington’s renowned cabinet members, Hamilton and Jefferson, were among the first of rival factions. Nevertheless, Washington sought to unify his colleagues for the sake of the nation. Although never officially joining the Federalist Party, he supported its programs to pay off all state and national debt, implement an effective tax system, create a national bank, and maintain good relations with Britain, preferring to remain neutral in the later wars of Europe. Washington guaranteed a decade of peace and profitable trade, with a vision of a great and powerful nation that would be built on republican lines using federal power. He sought to use the national government to improve and expand this new civil society, to found a capital city (later named Washington, D.C.), to promote knowledge and commerce, to reduce regional tensions and promote a spirit of American patriotism and unity. "The name of American," he said, must override any local attachments.

In September 1796, worn by burdens of the presidency, George Washington announced his decision not to seek a third term. Washington's “Farewell Address” was an influential primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against the forces of geographical sectionalism, political factionalism, and interference by foreign powers in the nation’s domestic affairs. This warning was principally concerning to him for the safety of the eight-year-old Constitution. He urged Americans to subordinate sectional jealousies to common national interests. Writing at a time before political parties had become accepted as vital extra-constitutional, opinion-focusing agencies, Washington feared that they carried the seeds of the nation’s destruction through petty factionalism. Although Washington was in no sense the father of American isolationism, since he recognized the necessity of temporary associations for “extraordinary emergencies,” he did counsel against the establishment of “permanent alliances with other countries,” connections that he warned would inevitably be subversive of America’s national interest. Washington’s concerns carry a timely message for all generations:

“The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that, from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

For this you have every inducement of sympathy and interest. Citizens by birth or choice of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together. The independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint councils and joint efforts – of common dangers, sufferings, and successes.

But these considerations, however powerfully they address themselves to your sensibility, are greatly outweighed by those which apply more immediately to your interest. Here every portion of our country finds the most commanding motives for carefully guarding and preserving the Union of the whole.”

Emphasizing the maintenance of Constitutionality:

“All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations under whatever plausible character with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction; to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the mirror of the ill concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common councils and modified by mutual interests. However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

Towards the preservation of your government and the permanency of your present happy state, it is requisite not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles, however specious the pretexts. One method of assault may be to effect in the forms of the Constitution alterations which will impair the energy of the system and thus to undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In all the changes to which you may be invited, remember that time and habit are at least as necessary to fix the true character of governments as of other human institutions, that experience is the surest standard by which to test the real tendency of the existing constitution of a country, that facility in changes upon the credit of mere hypotheses and opinion exposes to perpetual change from the endless variety of hypotheses and opinion; and remember, especially, that for the efficient management of your common interests in a country so extensive as ours, a government of as much vigor as is consistent with the perfect security of liberty is indispensable; liberty itself will find in such a government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest guardian. It is indeed little else than a name, where the government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.”

Washington even elaborated with predictions all too familiar:

“The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight) the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and the duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.”

In all capacities, and as a private citizen between and after his several public offices, Washington, more than any American contemporary, was the necessary condition of the independence and enduring union of the American states. It was in mere honest recognition of this that time bestowed upon him the epithet, ‘Father of our Country’, and that in 1799, upon his death at the age of 67, the memorial address presented on behalf of the Congress of the United States named him "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

Here’s to our First and Greatest President: George Washington.

Sources: Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, Wikipedia, U.S. Government Printing Office, PBS